Yiddish (Western)

Description by Auden Finch

Introduction

“Western Yiddish,” also known as Judeo-German, refers to a family of Yiddish dialects historically spoken in continental western Europe. Between the 14th and 19th centuries, Western Yiddish was the primary language spoken by Ashkenazi Jews living in what is today Germany, France, Switzerland, northern Italy, and the Netherlands. Western Yiddish is distinguished from Eastern Yiddish, which encompasses the Yiddish dialects originating in central and eastern Europe, such as Hungary, Poland, and Lithuania.

Names of language:

Western Yiddish, Judeo-German, yidish, yidishdaïtsch (Alsatian Yiddish and varieties), jüdisch-deutsch, judéo-alsacien, Judendeutsch, mayrev yidish, mayrevdik yidish, Westjiddisch

Territories where it was/is spoken:

Germany, France, Switzerland, northern Italy, the Netherlands

Estimated # speakers:

1900: 25,000

2024: No fluent speakers, a dozen heritage speakers

Vitality today:

Moribund (Swiss and Alsatian Yiddish), extinct (all other dialects)

Writing systems:

Hebrew characters, occasionally Latin alphabet

Literature:

Poetry, prose, theater, extensive print literature

Language family:

West Germanic

Quick Facts

History

While a Jewish presence in western Europe has been attested since the 4th century C.E., the first available source written in an early form of Western Yiddish dates to a 1272 inscription in the Worms Mahzor, which reads:

גוט טק אים בטגא ש ויר דיש מחזור אין בית הכנסת טרגט

gut tak im betage s vir dis mahzor in beys hakneyses trage

“May it be a good day for the one who carries this mahzor

(festival prayer book) into the beys hakneyses (synagogue).”

This short couplet marks the earliest extant example of a Germanic language written in Hebrew characters. Notably, nouns borrowed from Hebrew (mahzor and beys hakneyses) are integrated into the sentence alongside Germanic elements (see Shmeruk 1983: 100-103). Manuscript sources from the following centuries attest to the development of a specifically Jewish Germanic language, characterized by a largely Western Germanic vocabulary and heavy borrowing from Hebrew and Aramaic, written using a modified Hebrew alphabet (Fleischer 2019: 248).

As Ashkenazi Jews migrated throughout Europe, they developed different dialects of Yiddish in various regions. Over the centuries, this led to increased distinction between the Eastern and Western dialect families. Eastern Yiddish was characterized by lexical and grammatical influence from the surrounding Slavic languages. Vowel pronunciation between the Eastern and Western dialects diverged considerably. Western Yiddish dominated in printed Yiddish-language texts during the 16th-18th centuries, with large printing centers in Amsterdam and Venice. This literature paved the way for the modern Yiddish literary movements that would take root in Eastern Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Beginning in the late 18th century, Western Yiddish rapidly declined as a language of everyday use among Western European Ashkenazim. The process of Jewish emancipation and the opening of a path towards assimilation encouraged language shift away from Yiddish and towards standard German, Dutch, and (in the case of Alsace-Lorraine), French (Kahn 2016: 650-651). By the 20th century, only the Alsatian and Swiss varieties of Western Yiddish were still spoken in significant numbers. Since the mid-20th century, all dialects of Western Yiddish have virtually ceased to be spoken as languages of daily use (Fleischer 2019: 246), and only a few heritage semi-speakers remain.

Fragment from a 1567 letter from Jerusalem to Cairo, written in Western Yiddish by Rachel bas Avraham Zussman, a Jewish woman originally from Prague

Linguistic Components

Germanic

The vast majority of Western Yiddish vocabulary and grammar is Germanic in origin. Because of the lack of sufficient documentation of Western Yiddish as a spoken language, it is difficult to evaluate the grammar of colloquial Western Yiddish. The literary register contains some similarities to standard German not present in Eastern Yiddish. In particular, older Western Yiddish print sources exhibit the use of the simple past tense, such as דז וור doz var, meaning “that was,” as opposed to the Eastern Yiddish compound past form דאָס איז געװען dos iz geven, literally meaning “that has been.” Western Yiddish print sources also show the use of איין eyn or ayn as the indefinite article, as opposed to Eastern Yiddish אַ a. This indefinite article is sometimes included in the declension system, while Eastern Yiddish indefinite articles are never declined. Syntax between the two dialect families is largely similar, although Western Yiddish, like German, often uses SOV (subject, object, verb) word order for subordinate clauses, whereas Eastern Yiddish tends to use SVO (subject, verb, object) word order in all clauses.

Because these divergences appear in written sources only, and because they are not always used consistently (even within the same text), it is unclear whether they reflect actual dialectical features of Western Yiddish. It is possible that, as with the phenomenon of daytshmerish writing in Eastern Yiddish, Western Yiddish print sources affected their language to more closely resemble Standard German, the non-Jewish prestige language that surrounded most speakers of Western Yiddish.

Western Yiddish pronunciation differs significantly from Eastern Yiddish, particularly in its vowel system. The Eastern Yiddish diphthongs oy and ay correspond to the Western Yiddish au and aa respectively, with Western Yiddish generally tending towards increased vowel length. We see this especially in words derived from Hebrew or Aramaic, as in Eastern Yiddish beys oylem vs. Western Yiddish bays aulem, both deriving from Hebrew בית עולם beit olam meaning cemetery, lit. eternal home (For a detailed comparison of vowel systems in Western and Eastern Yiddish dialects, see Fleischer 2019: 293).

Romance Languages

As with Eastern Yiddish, Western Yiddish contains words originally absorbed from Romance languages. Although the exact patterns of migration are still debated, most linguists agree that Yiddish developed as an independent language in the medieval period after Jews from southern Europe settled in the German-speaking Rhine valley. These Jewish immigrants very likely spoke Jewish varieties of Romance languages such as French, Italian, and Provençal, and a number of words from these languages were maintained in Yiddish. From the Judeo-Italian benidicere, 'to bless', the verb bentshn ('to bless') is shared across all Yiddish dialects. However, when referring to other prayer practices (such as the morning prayers in a synagogue) Western Yiddish dialects use the verb oren from the Old Italian orare meaning 'to pray,' while Eastern Yiddish uses davenen (Fleischer 2019: 263), which likely stems from Hebrew davevan ('one who whispers'). Other verbs from Old Italian include planchenen, 'to cry', from plangere, and memeren, 'to search for words', from memere (Lévy 1954).

Hebrew

Western Yiddish includes a large number of words borrowed from Ashkenazi Hebrew. Some of these, such as maukem ('city') from מקום makom or kaf (village) from כפר k'far, referred to places. Others indicated types of people: bal sott (a secretive person) from בעל סוד ba'al sod, bal seï’chel (a wise person) from בעל שכל ba'al sechel, and bal gâwe (a prideful person) from בעל גאווה ba'al ge'ava. Hebrew nouns are integrated into the Germanic morphological system, often used as adjectives or compound nouns. These include words like unbetaamt ('tasteless', from Hebrew טעם ta’am, 'taste'), and yontefdig ('festive', from Hebrew יום טוב, 'holiday'), which are shared with Eastern Yiddish. However, a number of Hebrew-Germanic compound expressions appear unique to Western Yiddish: héinesmensch ('a charming person', from Hebrew חן chen, meaning 'grace' or 'beauty'), shéiker-sager ('liar', from Hebrew שקר, 'false'), and háser-kopf ('pighead', from Hebrew חזיר hazir, 'pig'). There are also some Hebrew words that have been integrated into verbs, for example the verb shashkenen to mean “to drink,” ultimately coming from the Hebrew שתה shata, or houleche “to go,” from the Hebrew הולך holech (Fleischer 2019: 262). Western Yiddish compound words formed from two Hebrew components follow German syntax, with the modifier coming first. For example, bores medine (lit. “cow country”), an Alsatian Yiddish nickname for Switzerland, is formed from the Hebrew words פּרות parot 'cows', and מדינה medina, 'country'. In Hebrew it would be expressed as מדינת פּרות medinat parot, with the modifier coming second and with the modified noun in the construct state.

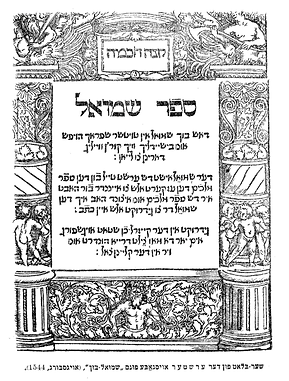

Shmuel-bukh (1544) title page (Wamsley, In Geveb, 2016)

Glikl from Hameln, Zikhroynes. “Ktiv” Project, The National Library of Israel, Jerusalem, Israel

Orthography

Western Yiddish was written using the Hebrew alphabet, although certain Hebrew letters were used only in specific cases. The letters תּ (tav), ת (sav), ח (khes), and כּ (kaf) were only used in words borrowed from Hebrew or Aramaic. However, unlike Eastern Yiddish, Western Yiddish orthography does use the letters שׂ (sin) and בֿ (veys) in words of Germanic origin. Vowels in Western Yiddish are usually represented by the letters א (aleph), ה (hey), ו (vov), י (yud), and ע (ayin), as in Eastern Yiddish, and words borrowed from Hebrew and Aramaic maintain their original vowel orthography. Diphthongs are written by combining vowel letters, including וי for ou or au and יי for ey, ay, or (more commonly) aa. Because Western Yiddish was dominant in the early Yiddish printing industry, its orthography influenced the eventual standard orthography of Eastern Yiddish. This is evidenced by the wide use of the letter שׂ sin in Eastern Yiddish printing until the mid-19th century, at which time it was generally replaced by ס samekh. Western Yiddish also often uses ו vav to represent the /f/ sound at the beginning of a word, such as in וראגן (frogn, 'to ask') or ורגעבן (fargebn, 'to forgive'), while Eastern Yiddish uses פֿ or פ fey.

Whereas Eastern Yiddish uses אַ and אָ to represent the pasekh and komets vowels, respectively, in texts that otherwise do not include full nikud, Western Yiddish sources typically either use nikud throughout a text to represent all vowels or do not use them at all, with the latter being more common. Western Yiddish typically uses א without nikud to represent the komets vowel, similar to many contemporary dialects of Hasidic Eastern Yiddish, while shva is often represented by yud. Pasekh vowels are typically not marked at all.

Western Yiddish literature in the Early Modern period (from roughly the 16th to late 18th centuries) comprised a large corpus of works on both secular and religious topics. These ranged from translations of and commentaries on the Hebrew Bible to chivalric romances. Adaptations of biblical narratives were often published in Yiddish verse, such as the Shmuel-bukh, a 16th-century adaptation of the Books of Samuel. Also popular were secular works based on texts with non-Jewish origins, the most well-known of these being the Bovo-bukh, an adaptation of the Italian Buovo d’Antona (Rosenzweig 2016).

Another significant work written in Western Yiddish is the memoirs of Glikl of Hameln, a Jewish woman living in northwestern Germany in the 17th and 18th centuries. These memoir sources in particular, along with business transactions and legal testimony recorded in Yiddish, provide invaluable insight into the daily lives of Jews living in Western Europe during the Early Modern period.

Literature

Bovo-bukh (1541) title page (Rosenzweig 2016)

Regional Varieties

Alsatian Yiddish

Alsatian Yiddish, also often referred to as Judeo-Alsatian, is the historical Western Yiddish dialect spoken by the Ashkenazi Jewish community living in Alsace-Lorraine in what is today Eastern France. Called yedischdaïtsch or judéo-alsacien by Alsatian Jews, this language reflects both general features of Western and Eastern Yiddish and influences from its surrounding non-Jewish cultures. Today, the language has almost completely receded from daily use as a vernacular language. However, the words and phrases that remain in use among heritage speakers reflect the unique history of Alsatian Jewry.

Alsatian Yiddish preserved older French vocabulary, even after these words fell into disuse among the non-Jewish French-speaking population. These include preien, “to invite,” from prier; frismel (noodles) from vermicelles; and pilzel (maid) from pucelle (Lévy 1954). These are examples of archaisms, a common feature of Jewish languages. In addition, terms related to technology and institutions that entered Alsace during the 19th and 20th centuries (train stations, cars, bicycles, etc.) are typically from French. As with speakers of other Jewish languages, Alsatian Yiddish speakers played creatively with the mix of linguistic material available to them. For example, the French phrase vingt-cinq, meaning 25, was used as an Alsatian Yiddish slang term for coffee; this is derived from the fact that the Hebrew numeral for 25, 'כה, is pronounced kaf hey, which sounds like the French café.

Humor

Alsatian Yiddish has attained a reputation as a language of humor. As the language has left daily vernacular use, jokes remain one of the strongest points of memory for heritage speakers. Hebrew terms were often used for comic effect, acquiring an ironic or humorous meaning when used in daily Alsatian Yiddish speech. For example, the word beïs, derived from the Hebrew word for house, בית, came to refer to an old building that was falling into disrepair. The word kolbo, from כל בו, a term that means “containing everything” and refers to prayer books that contain liturgy for all holidays, was used in Alsatian Yiddish to call someone a know-it-all.

Wenn der Schawess of e Méttwoch fällt.

“When Shabbat falls on a Wednesday.”

Schawess from שבת, the Jewish day of rest which lasts from sundown on Friday to sundown on Saturday

Used to indicate something that will never take place.

Rèwe ésch ké Massematten fer a Yétt.

“Being a rabbi is no business for a Jew.”

Rèwe from רבי rabi, Massematten from מַשָׂא וּמַתָן meaning “negotiation” (literally “burden and gift”)

Expresses the difficulty of leading a Jewish community and managing its disputes or

difficulties.

Unser Haryett scheckt die Refua for der Makke.

“God sends the healing before the beating.”

Refua from רפואה, meaning cure, Makke from מכה, meaning “blow” or “strike”

Used to praise good luck that arrives before it is necessary.

Ich hab e Bréf vom Elieu nôve, was schribt er? Er war of Dschüffe.

“I got a letter from Elijah the Prophet, what did he write? He’s waiting for a response/ repentance.”

Dschüffe from תשובה, meaning either “response” or “repentance.”

This play on words is often said on Yom Kippur.

Wenn m’r hittzutag nétt a bessele Ganef éch, kann m’r ka érlicher blaïwe!

“These days, if you’re not a bit of a thief, you can’t stay an honest man!”

Ganef from גנב, “thief”

Refers to the hypocrisy necessary to get ahead in business.

Source: Kahn 2022.

Livestock Trade

The image of the rural Alsatian Jewish livestock or cattle trader has become entrenched in the community’s self-conception of their history. These traders were called “Peïmesshaendler,” from Hebrew בהמות (Ashkenazi beheymes) and the Germanic Händler, meaning traders or merchants. The culture around the cattle trade led to a number of Alsatian Yiddish expressions and clichés:

Dü kânsch die Küeh kaûfe oder nétt, s’esch m’r ké hélig.

“You can buy the cow or not, it doesn’t matter to me.”

The first part of this sentence reflects the language’s Germanic component, while s’esch m’r ké hélig is derived partially from textual Hebrew: hélig originates from the Hebrew חילוק, hiluk, meaning “difference.” Compare to Eastern Yiddish es makht nisht kayn khilek, “it makes no difference.”

Isch wôhn néhmi inn e Kaf.

“I don’t live in a village anymore.”

“Kaf” is derived from Hebrew כפר kfar, village. This phrase was associated with upwardly mobile merchants, many of them cattle traders, who moved to larger cities and took outsized pride in abandoning their humbler roots.

Der kommt von de Kühwadel Aristokratie!

“This one comes from the cow-tail aristocracy!”

On the other hand, this phrase was used to mock cattle traders who had achieved economic success and attempted to either hide or minimize the means by which they acquired their wealth. Unlike the French aristocracy, Alsatian Jews had not historically been permitted to own land, so any affluence came from less glamorous economic endeavors (like the cattle trade), rather than from grand estates or royal titles.

Source: Kahn, Alain. 350 expressions judéo-alsaciennes traduites et commenteés

(Strasbourg: La Nuée Bleue: 2022), 162-173.

A Jewish cattle trader, sketched by the Jewish Alsatian artist Alphonse Lévy (1843-1918)

Rosh Hashanah Poem in Alsatian Yiddish (1946)

Swiss Yiddish

From 1678 until the mid-19th century, Swiss Jews were restricted to living in two small towns, Endingen and Lengnau in the Surbtal Valley. This led to the emergence of a unique Swiss dialect of Western Yiddish, often called Surbtaler Yiddish after the valley where its speakers had settled. Surbtaler Yiddish is quite similar to Alsatian Yiddish, owing to the fact that both were influenced to some extent by the surrounding Alemannic German dialects. Swiss Jews, like their Alsatian counterparts, were also involved in the cattle trade and shared many of the idioms and expressions characteristic of the jargon of Jewish livestock traders.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Swiss-Jewish linguist Florence Guggenheim-Grünberg recorded a number of interviews with elderly speakers of the Yiddish dialects spoken in Lengnau and Endigen (Fleischer 2019: 268). A selection of these interviews, which also detail some of the unique local Jewish traditions, is available here.

Owing to the prominence of Swiss and Alsatian Jews as traders of cattle and other livestock, Swiss Alsatian Yiddish vocabulary seeped into the Viehhändlersprache, the jargon of cattle traders throughout Alsace-Lorraine, Germany, and Switzerland. This included the use of Hebrew numerals (א Aleph = 1, ב Bet/Beys = 2, etc.) to count livestock at markets, as well as Hebrew-derived terms that referred to cows of different ages, sizes, and genders. Swiss and Alsatian Yiddish vocabulary became so ubiquitous that printed glossaries of relevant terms were distributed to non-Jewish livestock merchants well into the mid-20th century (Matras 2010).

East Frisian Yiddish

An additional local variety of Western Yiddish was spoken by the Jewish community living in East Frisia (Ostfriesland), a coastal region in northwest Germany. East Frisian Yiddish is best attested in the town of Aurich and remained spoken as a daily language until the Holocaust. For more information, see Gertrud Reershemius’ 2007 monograph Die Sprache der Auricher Juden: zur Rekonstruktion westjiddischer Sprachreste in Ostfriesland.

Lekoudesch

In southwestern Germany, a dialect called Lekoudesch or Lotegorisch, a name derived from the Western Yiddish phrase לשון קדוש loshn kaudesh, developed through language contact between Western Yiddish-speaking cattle traders and local non-Jewish speakers of German. Western Yiddish words were often absorbed into dialects spoken by the non-Jewish population in this region. For example, the town of Rexingen in Baden-Württemberg was nicknamed “Siggesmauchem,” from the Western Yiddish סוכות מקום, sukes maukem, literally “Sukkot place” (Götz 2008). Similarly, the local dialect spoken in the town of Schopfloch in the Franconia region of northern Bavaria incorporates terms borrowed from Western Yiddish-speaking Jews living and working in the region. Called lachoudisch (also derived from לשון קודש lashon kodesh), this dialect is still spoken by some elderly non-Jewish residents (see Matras 2010). A 2023 television report from Franken Fernsehen depicts the legacy of lachoudisch in Schopfloch and its continued use as a marker of local identity.

German glossary of terms used by Jewish cattle-traders (Germany, early 20th century)

Status

With the exception of some older heritage speakers who have some competence in the Alsatian and Swiss dialects of Western Yiddish, Western Yiddish is rarely spoken as a living language (Fleischer 2019: 246-247). Scholarship around the language has led to some degree of postvernacular engagement, particularly in the field of music. Because so much of the Western Yiddish literary corpus is written in verse, these sources lend themselves well to musical settings.

In some cases, single words have lived on in the Jewish communities where Western Yiddish was once spoken. For example, the word barkhes, referring to a braided Shabbat bread similar to Challah, is still sometimes used among Alsatian and some German Jews (see Maler 1979: 1-5 for more).

Western Yiddish music by Simkhat HaNefesh

Share this page on your socials:

To cite: Finch, Auden. n.d. Yiddish. Jewish Language Website, Sarah Bunin Benor (ed.). Los Angeles: Jewish Language Project. https://www.jewishlanguages.org/western-yiddish. Attribution: Creative Commons Share-Alike 4.0 International.